By Jeremy H.

Hello Mama Maven readers. I’m Jeremy and new here at The Mama Maven. Recently, our editor Nancy sent me to “World Maker Faire 2017” as “Mama Maven for a day” to take some pictures, follow my son Elijah around, and generally be media-savvy on her behalf, looking for good finds. Do You Have What it Takes to be a Maker Parent? Hint: It’s Not Money | The Mama Maven Blog

What happened at the Maker Faire was far more than that, when other maker parents started to tell me about how they felt, and how they coped with kids who sometimes out-smarted or out-earned them, and who were becoming recognized in public for being “Maker Celebrities.”

To introduce myself, let me elaborate.

This year marked the second anniversary of becoming a “maker-parent.” The years have been unexpected, from my son Elijah unboxing his first raspberry pi to being covered by Make Magazine and becoming part of the “make family.” Elijah has developed into an engineer who is solving his own problems. Parenting books left out this part, for our family adjusting to a “maker kid” has been joyful, and it has also been full of new challenges.

The transition has changed the parent-child dynamic around here in a positive way that is redefining parenting, redefining adolescence, and challenging parental complacency. In many ways becoming a maker-parent has both literally and figuratively given us the tools we need to get through these middle school years. We now know how to deal with big wins and big disappointments alike, but we didn’t start there.

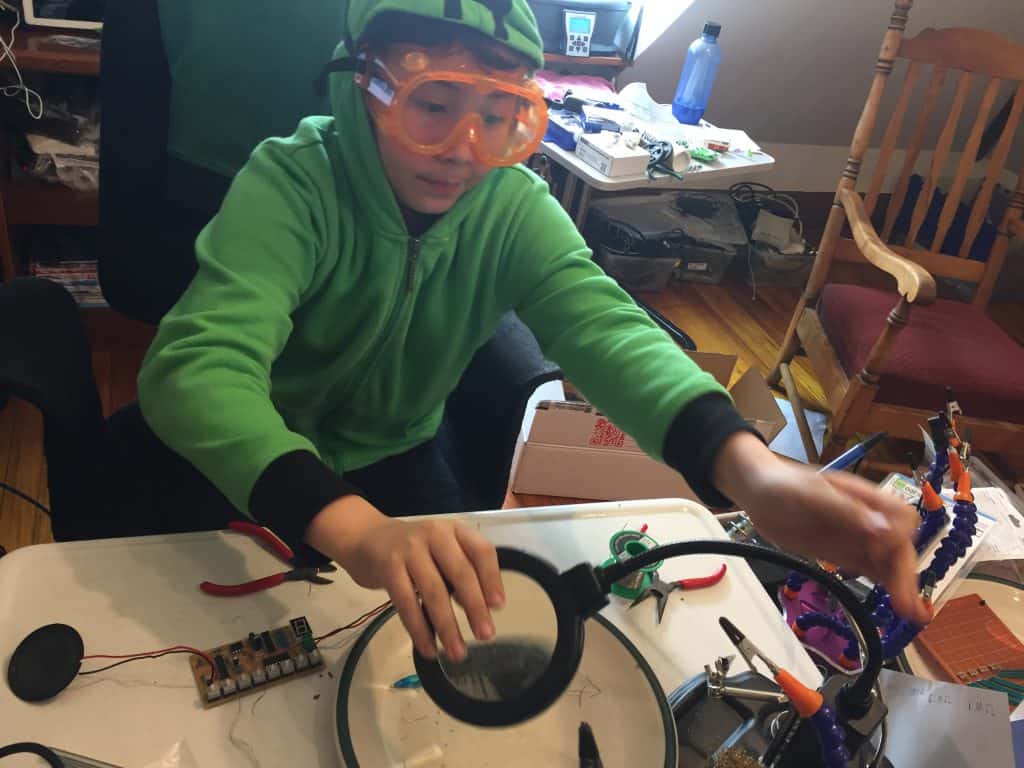

In August 2015, Elijah came home from a “residential” camp program. He had a dorm room, classes, trips, and activities. It was like a camp mixed with a college introduction program. When he got home, he had a question. “Do you know how to use a soldering iron?” “Why?” was the immediate reply, while at the same time considering that this sounds dangerous.

“One of the kids in my program built a backpack circuit project and got a patent.” “So you want to make a backpack” was the easy way to try and unwrap his request. “NO” he emphatically added, “I want a patent!” Keeping a step in front of this looked hard to do, but I had no idea how hard it would be, and I was afraid it would be expensive. I’m thrilled to report it was not nearly as expensive as I’d feared.

As it turns out, we did have an old soldering kit sitting around, but it just didn’t seem enough to get started. As I was trying to figure it all out, Elijah decided it was time to make a high-altitude balloon to see at which height he could see the world curve. Prevailing conventional wisdom suggested we needed to learn about something called an “Arduino” but there were many models to choose and their different uses were ambiguous.

Elijah came along for our first visit to “TinkerSphere,” a maker-supplies store in the East Village section of Manhattan, in New York City. We found them with a google search. The woman behind the counter was able to answer all my questions and more, she started asking about my sill level and about Elijah’s. Being interviewed, even grilled a little bit by a salesperson less than half my age was humbling.

“You need a Raspberry Pi, not an Arduino” she said. It’s hard being wrong, but there’s a parental protocol which covers this, called “lunch.” One quick meal at BareBurger later, and a little time reading on the phone, and it was time to go back to the store. All prior research was going out the window, but this Pi thing looked like it could do the job better. At less than half the cost of an intel Arduino board, it seemed like a good bet.

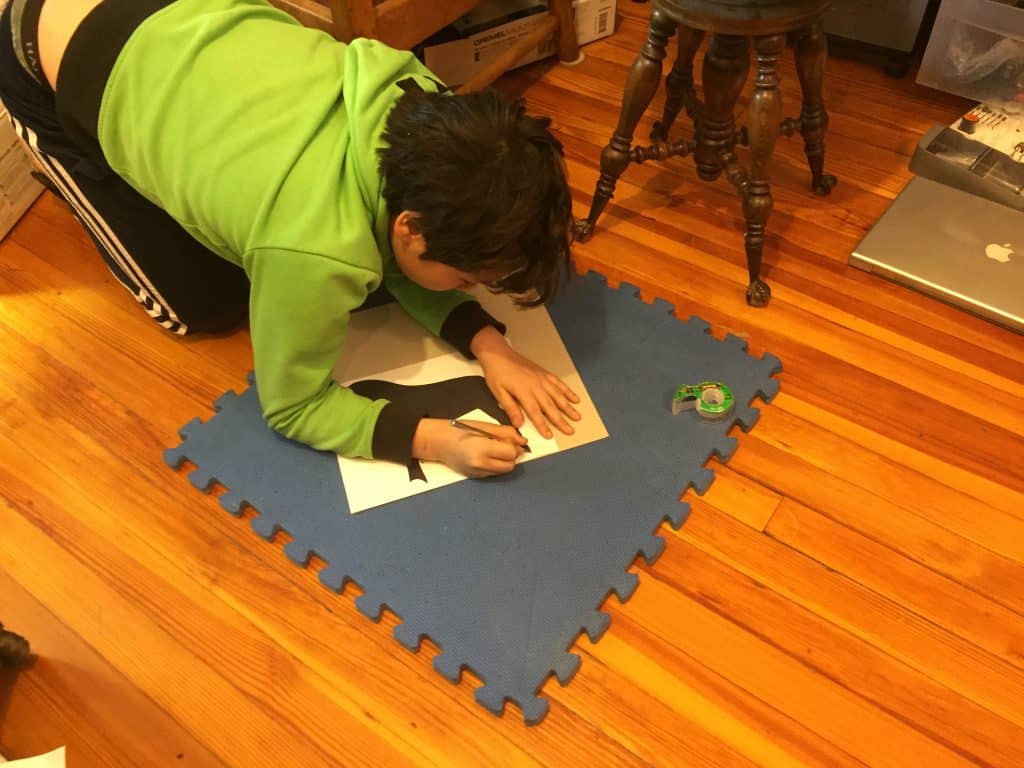

That night Elijah went from unboxing his new toy, to installing a basic OS called “Raspbian,” then on to playing Minecraft on it. Before going to sleep, Elijah surprised us by wiring an LED to the pins on the Raspberry Pi and blinking it on command in a program written in “python.” The next day he picked up the existing soldering kit and put together a croaky sounding keyboard before making his LEDs dance like the front of the car from “Knight Rider.”

The Raspberry Pi kept on giving great projects just by using google more. He quickly needed more stuff to solder, so it was back to TinkerSphere, to get another few kits. He chose a Menorah from Evil Mad Scientist and a Volume meter (Vµ) meter from Velleman. With his Menorah, he started to teach other kids how to solder starting with his friend Marwah. From his many attempts at the volume meter, he eventually made contacts and friends inside Velleman. He’s made friends with the woman who designed the menorah now, too. These kits were $5-$20 each, less when you use Amazon Prime.

At this point, the realization was that we had a “maker kid”. He quickly went beyond where local STEM classes and programs could take his skills and was going strong on his own merit. This was a phase in parenting that was not planned – how to keep a kid grounded as he was gaining media attention and growing a serious set of nearly professional level skills?

At this point, the realization was that we had a “maker kid”. He quickly went beyond where local STEM classes and programs could take his skills and was going strong on his own merit. This was a phase in parenting that was not planned – how to keep a kid grounded as he was gaining media attention and growing a serious set of nearly professional level skills?

Elijah is an only child, so being his de-facto difficult older brother as well as his dad was already a challenging job. “Teacher” really didn’t seem to be the best role either, half the time he would need help getting a project done when it was over both of our heads. Without Google, keeping up would have been impossible, but research skills go a long way.

Learning to be your kid’s “coach” instead of their teacher is a big job for a parent. You need to be ready to change roles quickly. Kids like Elijah have a process that can involve yelling at a project, crying and even injuries. He works with things that heat to over 300c and that means he gets burns now and then.

Elijah has become fiercely independent, not letting anyone help with his more recent projects at all beyond basic advice and company while he works. He is super critical of himself. His meltdowns run even hotter than his soldering iron. Being of comfort has become more important than being a “smart dad.” He wins competitions as much as he doesn’t win them and helping him manage being a good sport when winning might just be more difficult than helping him lose gracefully.

Elijah has become fiercely independent, not letting anyone help with his more recent projects at all beyond basic advice and company while he works. He is super critical of himself. His meltdowns run even hotter than his soldering iron. Being of comfort has become more important than being a “smart dad.” He wins competitions as much as he doesn’t win them and helping him manage being a good sport when winning might just be more difficult than helping him lose gracefully.

Kids handle disappointment well for the most part, it’s helping them be grateful in victory that has been the tougher job.

Stuff breaks. Sometimes stuff just doesn’t work. Not getting emotionally involved in the process has been a steep learning curve. Taking a step back and remembering that teaching is not the same as coaching can be as hard as letting him take his first solo subway ride. It’s been the only way to manage the roller coaster ride of a young engineer of the “Digital/Internet Native Kids” (DINK) age so far.

It hasn’t been easy for Elijah either. His school is really geared more toward sports and his friends and peers have shown only a little interest in his new habits and hobbies. He feels that if he were a basketball player his friends and school would support him more in competitions and at shows. He asked one of his oldest friends “Do you know python?” His friend replied by trying to speak like a snake from Harry Potter.

Becoming a maker parent took a lot of adjustment, but there was luck involved in that the skills required were already a part of my background in software development. It was not hard to get just enough ahead of Elijah to stay a good “coach.” For his grandparents it was harder – one year he wanted Star Wars and Minecraft toys and the next year he was designing laser platforms and video games and 3d printing his own star wars toys.

Becoming a maker parent took a lot of adjustment, but there was luck involved in that the skills required were already a part of my background in software development. It was not hard to get just enough ahead of Elijah to stay a good “coach.” For his grandparents it was harder – one year he wanted Star Wars and Minecraft toys and the next year he was designing laser platforms and video games and 3d printing his own star wars toys.

Elijah has been in magazine articles, awards, trade shows, alliances, sponsors… the things you can expect when things go right. If you are interested to see what he does, his work is available at www.notabomb.org.

Elijah has been in magazine articles, awards, trade shows, alliances, sponsors… the things you can expect when things go right. If you are interested to see what he does, his work is available at www.notabomb.org.

My next postP: Following a maker kid around Maker Faire.

[…] Do You Have What it Takes to be a Maker Parent? Hint: It’s Not Money […]